Thomson Newspapers - Part I

“He said it was going to say on his tombstone that he bought newspapers in order to make more money in order to buy more newspapers and so on” – Buffett

Introduction

Thomson Newspapers (TNL) was one of the great rollups of the 20th century. It turned Roy Thomson, who grew up in a working-class family in Toronto, into one of the richest people in the world. Ken, Roy’s son who inherited and expanded the empire, may actually have been the world’s richest person at some point in the 1980s. What makes this story even more interesting is that Roy became so incredibly wealthy despite having been a late bloomer. Roy was frequently on the verge of insolvency in his 30s, was 40 years old when he purchased his first small-town newspaper, and didn’t make serious money until his mid 40s. But once TNL became profitable, it compounded ferociously.

Roy Thomson is one of the GOATs. While the case study in this two-part series is about TNL during the post-Roy-Thomson years, we can’t resist the urge to share a bit of background upfront about Roy Thomson and TNL under his leadership. (We encourage readers to check out Russell Braddon’s biography of Roy Thomson as well as Roy Thomson’s autobiography “After I Was Sixty”.) The case study in Part II covers how TNL evolved over the subsequent three-and-a-half decades under professional management, until it started selling its newspaper operations.

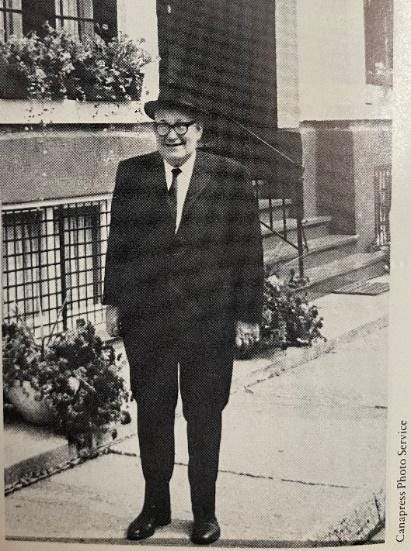

Roy Thomson, aka Lord Thomson of Fleet Street

Life before Newspapers

An important early influence in Roy’s life was Aunt Hislop. While Roy’s parents were poor, Aunt Hislop was very wealthy by virtue of buying second mortgages at a discount. Roy had dropped out of high school at age thirteen and attended Mr. Elliot’s Business College for a year to study bookkeeping. When Roy found out that Aunt Hislop kept no ledgers for her business, he was distraught and urged her to let him bring order to chaos. Not many fourteen-year-old boys would derive pleasure from drawing up ledgers and recording hundreds of journal entries, but Roy thrived on this task:

“Eventually [he] so mastered the details of his aunt's affairs that at any moment he could tell her what she was worth, how much she was owed, and which payments had been made when by whom.”

Aunt Hislop returned the favor by letting fifteen-year-old Roy co-invest in the purchase of some mortgages. This kicked Roy’s ambitions into higher gear. Instead of chasing girls like the other boys, he spent all his time figuring out how to reinvest the profits from his mortgage investment. This ‘business-first’ mindset would persist for the remainder of his teenage years until he met Edna, his future wife, at the age of 20. It’s interesting to see his mind already so wrapped up in the pursuit of making money at an age when having fun is usually the number one priority.

While he started off well with Aunt Hislop, the theme of Roy’s entrepreneurial endeavors prior to newspapers was one of constant struggle. He became a farmer out of youthful naivete but moved on quickly, losing most of his capital in the process (he was worth about $170,000 USD in today’s dollars when he purchased the farm). His first auto parts distributor had to be wound down due to a liquidity crunch (he sold too many auto parts to customers who were slow to pay while suppliers expected timely payments). His second auto parts distributor worked out o.k. but the rewards did not justify the efforts, so he moved on. He had a radio distribution franchise in Ottawa with DFC, a radio manufacturer, but DFC decided to take back its Ottawa franchise to deal there directly. The North Bay radio distribution franchise was a struggle as there was no reception of the far-away big-city radio stations and the Depression was not a great backdrop for selling expensive radios to households. To tackle the reception issue, he founded a radio station in North Bay but lacked the capital to properly fund it so that it spent years on the verge of insolvency. Basically, Roy could not catch a break for 20 years.

Capacity to suffer

Roy had the character traits that you would expect from someone who was that successful in business. He was incredibly driven and single-minded. He sacrificed much family time for work and didn’t have any hobbies. He liked to say that he would “rather read a balance sheet than a book” and would show off his balance sheets to anyone willing to look at them. When he was getting close to passing the North American business onto Ken in the 1950s, he summed it up as follows: "Ken, if you're going to run this business one day, you've got to give up almost everything else. You've got to go to parties you don't want to go to, meet people you don't want to meet. You're going to have tremendous responsibilities to live up to. You've got to be a slave to your business. I am - but I like it. It has compensations, even though the business runs you, not you it." Late in life, he told an interviewer “I never really realized how narrow my interests are in life until I sat in the House of Lords where they have to discuss so many different subjects of which I know almost nothing.”

Roy Thomson also had a Steve Jobs-esque reality distortion field. Years of training as a salesman, particularly trying to sell high-ticket luxuries such as refrigerators, washing machines and radios during the Depression, had honed his negotiation skills and taught him how to apply his disarming charm.1

What we found most interesting though was his capacity to suffer. It seems as though it wasn’t a conscious capacity to suffer (i.e. thinking “this sucks” but persevering) but rather an unending optimism together with bathtub memory. He was a dreamer, driven by the success he saw so clearly in his near future, and never stewed on failures. These dreams were at times far removed from reality. In a way he reminds us of Alex Honnold who famously climbed about 3,000 feet without a harness, able to zone out emotions that would cripple 99.99% of people. A few anecdotes:

When his first auto parts distributor had to be liquidated in 1925, the only one involved who seemed unperturbed and ready to move onto the next venture was Roy. “[He] set out, full of optimism, for Ottawa where, he had already convinced himself, there lay a market that was virtually untouched…”

Becoming a millionaire (~$20m in today’s dollars) was Roy’s North Star during the first half of his life. He first announced this goal when he was seventeen years old and would repeat it endlessly. He mentioned once again that he would soon be a millionaire during his first press interview in his mid-to-late 30s. Notably, he said this at a time when (1) one of his companies was close to bankruptcy, (2) the radio franchisor was “tidying up Roy’s [past due] accounts”, and (3) he was unable to live up to his promise to pay the car loan instalments of one of his employees. His wife, Edna, reacted by sobbing “What a crazy thing to say. We can’t even pay for the milk.”

Then there’s a story that struck a personal chord with us. Later in life, in his late 50s, Roy ran as Progressive Conservative Candidate in the northern part of Toronto. Anyone who has ever canvassed will know that it is an utterly draining experience. After canvassing about 100 homes some time ago, Yours Truly were ready for a vacation. Not Roy Thomson. “His party workers described him as an exhausting one, who insisted on waddling down every street, knocking on every door and personally talking, they estimated, to more than twenty thousand (!) householders.” It gets even better: “Knowing that constituents hated having their dinner hour interrupted, he gave up canvassing at 5.30 p.m., slept for several hours and then, returning to the fray at about eight o'clock, scurried from door to door until he found that he was getting people out of bed, which they disliked even more than being dragged from their dinner table.” He did all that despite knowing well in advance from the polls that he was very likely to lose (which he did).

Lastly, one just has to look at the simple fact that Roy sustained his exhausting entrepreneurial efforts despite very little success for about 20 years. Any regular human being would long have sought refuge in gainful employment.

All of this goes to show that Roy had a near in-human capacity to suffer and a lot of energy. Once he found a fertile hunting ground, the newspaper industry, the outcome was predestined.

Thomson Newspapers 1934 – 1952: The Roy Thomson Years

Roy had figured out the power of advertising in a monopoly position due to his experience with small-town radio stations. He had seen first-hand how getting one retailer in town to advertise on his station meant that everyone else had to advertise as well. He also learned that, despite complaining bitterly, there was little merchants could do if he raised prices. Roy was always “figuring”, i.e. analyzing how businesses around him made money, so it wasn’t long before he recognized that “newspapers, not radio stations, were the real source of advertising wealth.” Already before buying his first newspaper company, he had a habit of measuring the editorial-to-ads ratio in newspapers he came across.

Unless otherwise noted, the following quotes in this section are from Russell Braddon’s biography (emphasis ours).

Roy Thomson’s Thesis

What follows is Roy Thomson’s thesis as he presented it to Wood Gundy in the 1940s in order to issue his first debenture. This is about ten years after he bought his first newspaper and he owned close to ten papers at the time:

“The background, he pointed out, was historical and sociological. Canada had developed, especially in Ontario, along the routes of her railway lines. About every twenty miles along these lines an initial distributing centre had grown into a township of fifteen thousand or more people. Each township, very early, had developed its own small, weekly newspapers. As the town grew, so did its economy, until, in most of these towns, these weekly papers had prospered sufficiently to become dailies--one of which, in time, had usually ousted the rest. Most of these daily papers had for decades been in the hands of the one family, passed down from father to son, and had continued in existence more out of habit than conviction; and often, because they were run on uneconomic and old-fashioned lines, they nowadays made little or no money. Yet they were subject to succession duties each time the current publisher died, and these death duties were steadily whittling away what little incentive still existed for a family to continue the business. Therefore, Thomson concluded, there should, throughout Canada, be a great number of old family newspapers which, sooner or later, to the advantage both of the family and himself, he could buy. And they were properties worth buying because, in a company like his, it could be ensured that they would never be subject to death duties; and because every community in Canada was a growing one, becoming daily more prosperous; and because a single paper in such a growing, increasingly prosperous community represented an ineradicable monopoly - a cul-de-sac, as it were - into which must flow all of its advertising revenue; and because efficient, business-like publishing methods, such as he, almost alone in Canada, had perfected, must enormously increase the earnings and profits of any newspaper he acquired.”

Roy’s thesis was simple but spot on and TNL rode this wave over the ensuing four decades.

Learning the Ropes

Back in the day, it was a lot harder to conduct competitive due diligence. Roy had no background in newspapers yet would in short order develop better systems than any other newspaper company in North America, including publishing families that had been in the trade for decades. We found this to be an interesting example of Roy’s ingenuity:

“He drew a hundred dimes from the bank, looked up the names of a hundred cities in America that were approximately the same size as Timmins (whose population then was about fifteen thousand) and sent a dime to a newspaper office in each such town asking the publisher to mail him back a copy of his journal. Then, on the floors of his lodging rooms in Timmins, of the Spruce Street "office" and of his North Bay home, he went about the systematic task of measuring, analysing and charting--most particularly charting--all his conclusions about the make-up and earning power of small rural newspapers. From that moment onwards, his researches completed, Thomson the publisher knew exactly the proportions he wanted in his newspaper of classified and display advertising, of editorial comment and news and illustration.”

Roy Thomson’s Playbook

“He evolved formulae for deciding how much he was prepared to pay for any newspaper that came up for sale (making his decisions entirely on the evidence of figures, not bothering to visit and inspect the property he hoped to buy) and for improving that newspaper once he had purchased it.

Quite openly he confessed that what he required, if he was to buy a newspaper, was that it be the only newspaper (preferably a daily, although a weekly would do) in a town with a population of fifteen thousand (or more) in which at least one store was prepared to run a daily advertisement for which it would pay not less than one hundred dollars. These factors, plus Canadian Press's wire service, at a price reasonably related to cash flow, would induce him to buy.

Having bought, he would, as quickly as was economically feasible, install the best equipment (whilst leaving the staff intact), turn weeklies into dailies (which brought the community more prestige, which brought more trade, which brought more classified advertisements for the converted newspaper) and rationalise. About this rationalising process, he admitted, there were invariably complaints. No newly purchased paper ever wanted, after years of muddling along, to have imposed upon it a budget for every job and every item. "We're different here," he found his latest acquisitions always pleading: to which invariably he retorted: "Everyone's different - until you've figured 'em out." In the budget which he imposed on each of his papers, there was a salary for every job, and this salary could not be exceeded. If a man in such a job could get a better salary elsewhere, let him leave. He would be bettering himself, and that was good reason for him to leave: but to offer him more than the budgeted figure as an inducement to stay would be to unbalance the entire system and that was not, in Thomson's mind, good business. But his budgets did not stop at salaries; they covered everything. They prescribed, among many other things, how much metal (which frequently had been stolen in days past) should be used in the printing of an average page; how much in dollars and cents, per page per month, might be spent on the repairing and maintenance of composing machines; how much per hundred pages was available for the purchase of such unlikely items as glue, tape and string; how many man-hours production per page were permissible; how much could justifiably be put down to felt, gummed tape, oil and grease; and the amount per mile that reporters could claim for their own cars, in the absence of a staff car.

Immediately after it was purchased, it had to record the facts of its own economic existence in a standardised manner so that the expense incurred for any item could, at a glance, be compared (at the same place on the same page of the next account) with that of any other Thomson newspaper. If it was lower than the norm, then the norm might need adjusting; but if it was higher, then the publisher must explain.

Thomson could tell in seconds, by the examination in meticulous detail of like with like, exactly how each of his properties was progressing. If they spent a dollar a month more on lead or typewriter ribbons or notebooks for reporters than the budget prescribed, they must answer to him.”

When Buffett asked Thomson how he figured out the limit of his papers’ pricing power, Thomson told him that he instructed his managers to make 45% pretax2. Only above that level were you probably price gouging.3

In summary, TNL was run exceptionally well. Decentralized operations (head office never interfered with editorial) combined with a culture of measurement and accountability. A collection of talented managers. Respect for capital. To top it off, it was run by an “intelligent fanatic”.

Deal Flow

By nature of being viewed as family heirlooms (run for political clout rather than profits), buying up newspapers in the ‘40s and ‘50s required some hustle. Not infrequently, publishing families were offended at the mere inquiry whether their paper was available for sale.

Roy was a tireless networker. He worked his way up the ranks of the two industry associations, the Canadian Press (CP) and the Canadian Newspaper Publishers Association. He eventually became president of the Albany club. He was constantly meeting people and joining this board or that board. It became his habit to ask any publisher he met whether his newspaper was up for sale. Anyone even remotely considering the possibility of selling his newspaper knew that Roy was ready to buy.

“On the last afternoon of a CP conference, a publisher stood up and lamented, ‘Circulation is down… TV is killing us... Radio newscasts steal our stories… labour demands are endless… costs are rising… advertising revenue is falling…’ All of this for some ten minutes before, amid a profound gloom, he fell back on to his seat. At once Thomson, the dignified, hard-working, far-sighted and impartial president, was on his feet, eyes shining behind his bottle-bottom glasses, a sweet smile of sympathy on his lips. ‘Want to sell?’ he asked.”

As the game got harder over time, Roy became stealthier:

“As he bought more papers, Thomson developed a technique that kept newspaper owners from being tipped off about his interest in acquiring their paper. Much of the scouting was delegated to Thomas Wilson, who was given the sort of instructions an undercover agent might receive. ‘I was told to go by train rather than by car because my license plates might give me away. I was also told at which hotel to stay, and to meet the publisher some place other than the hotel so his employees would not know about the negotiations.’”

The Handover

Roy’s wife died of cancer in 1952 when Roy was ~58 years old. At this point, Roy was ready to hand the North American operations over to his son Ken and move onto the next act of his life4. After his run for Progressive Conservative Candidate failed, he purchased Scotland’s prestigious national newspaper, The Scotsman. His intention was to spend the remainder of his working days turning around the Scotsman and dialing his work intensity down a notch. However, a leopard doesn’t change its spots. As detailed in his autobiography, Roy went on to conquer the business and social world in the U.K.5

At this point, Roy had built TNL to critical mass. When he handed it over to Ken (effectively a non-executive chairman) and his lieutenants (Sid Chapman, St. Clair McCabe and John Tory) in 1952, TNL owned ~23 newspapers. Most of the papers were in small Canadian towns but the expansion into small U.S. towns had already begun. While the real expansion happened under Ken and his executives (TNL would grow to 168 newspapers by the time its profits peaked ~1988), Roy had built the perpetual motion machine which was the hardest part. Financing acquisitions had been a struggle, convincing families to sell was a grind, and operational processes had all been built from scratch.

The next post, Thomson Newspapers – Part II, contains our case study of TNL.

A couple anecdotes regarding Roy’s reality distortion field:

- During the years when his radio station was on the verge of insolvency, he managed numerous times to convince people to give up their well-paying jobs, accept a large pay-cut and hitch their wagon to his struggling company. This happened despite everyone knowing the company’s precarious financial position. “Thomson employees had become persons of considerable financial initiative who rarely bothered going near a bank. They went instead to Emile Brunette, the taxi driver, or to the cigar store round the corner, or to Bert Sutherland, the druggist. Each employee, in fact, had his own jealously guarded private banker [to cash the pay cheques], to whom, of course, was owed the duty of advice the instant Thomson's official bank had funds enough to cover any cheques outstanding.”

- When Thomson bought his first newspaper, there was just one hitch – he didn’t have the cash. This did not stop him though: “Thomson then met Bartleman and his partner Ryan, at their lawyer's office, to draw up a contract for the purchase of the Press. “Where’s your money?” the lawyer asked briskly. “I haven't got cash,” Thomson replied equally briskly. “Tell you what I'll do, though. I'll give you two hundred dollars down, and twenty-eight promissory notes of two hundred dollars each, repayable over twenty-eight months.” “That's a hell of a deal,” Bartleman protested. “Lookit.” Thomson pointed out, "I'm going to make a good newspaper out of the Press. Now if I go broke, you get the paper back; and if I don't, you get your money. Either way, you can't lose.” That’s how Thomson got his first newspaper with a 3% down-payment. He never ended up paying cash for the other $5.8k and instead convinced Bartleman and Ryan to take shares (lucrative in hindsight, but a hard sell at the time).

He may instead have said 40% pretax. We’ve come across two transcripts and one claims 40% while the other claims 45%.

Buffett used TNL as “The Excellent Company” in his case study at Notre Dame

Roy’s explanation as per Russell Braddon’s book: “Thomson explained that he had three reasons for going. First, by leaving Canada he would allow his son to develop; second, if he stayed in Canada he would only repeat endlessly what he had already done often enough, so that the challenge of it would vanish; and third… ‘I want to find out if I'm as good as I think I am.’"

A one-hour documentary about Thomson filmed during this time that gives you a sense of his hustle: https://www.nfb.ca/film/never_a_backward_step/