Studying Serial Acquirers

Scott Management wrote a foundational piece about serial acquirers.

http://scottlp.com/letters.html#Acquirers

It’s easily the best one we’ve come across and does a fantastic job of defining and categorizing serial acquirers, laying out why they’re attractive, and what one should broadly be looking for. If you haven’t read it yet, we highly recommend it because we’ll be borrowing concepts from that piece.

The tldr version:

Serial acquirers can be bucketed into roll-ups, platforms, accumulators and hold-cos.

Hold-cos are on one end, holding largely unrelated businesses with no synergies (i.e. BRK or IAC)

Roll-ups are on the other end, focusing on one homogenous vertical with very high scale driven synergies (i.e. TCI/Charter or Waste Connections/GFL)

Platforms (like FirstService or Danaher) have a few specific platforms, inside which they are more tightly integrated and resemble “lite” roll-ups with some synergies, but mostly focus on improvement through high knowledge/skills transfer

Accumulators (like Constellation Software) allocate capital broadly within many verticals in which they can acquire expertise but do not integrate or chase synergies

Platforms and accumulators hold the most promise for long-term capital compounding

There are some tell-tale signs of great serial acquirers, mainly around qualitative factors: structures, processes and best practices.

In our opinion, the line between platforms and accumulators is a bit blurry – some companies fall in-between, like Lifco, and sometimes accumulators evolve into platforms, like Halma. We’d also add one bucket to Scott LP’s categorization. “Portfolio” serial acquirers like Charles River and Stryker, which fall between Roll-up and Platform. These companies buy other firms/technologies primarily for the revenue synergies of being able to add incremental products into their highly efficient sales organizations.

Investors’ growing love affair with compounders over the last several years means that the one aspect that’s changed since Ryan Krafft originally wrote the piece is that buying platforms and accumulators isn’t like shooting fish in a barrel anymore. The average NTM PE ratio of the companies in the above database of high performance serial acquirers was ~21X in 2016, 5 years ago. Today it is ~36X.

Step one was to recognize that there are a lot of special platforms and accumulators out there, step two will be to understand which ones are best positioning themselves to scale long-term and are worth paying up for today. Scaling - deploying more cash flow for longer at high returns on incremental capital - is key.

Some more thoughts on why (good) serial acquirers are special

The allure of investing in a serial acquirer is the tendency of such companies to reinvest all or most of their free cash flow for a very long time at high rates of return. It’s as simple as that.

Serial acquirers (excluding the roll-ups, which are just one business vertical across many geographies) also have the added benefit of becoming more diversified businesses over time. Therefore, a very good serial acquirer can compound at high rates of return over time and simultaneously have less idiosyncratic risk, making it easier to never sell and let the position size swell with success. Danaher, Roper, Berkshire and Constellation are today a very diverse collection of earnings streams with different end markets and drivers.

Investors often look for companies that are heavy repurchasers of their own stock. The leveraged buyback model can be really powerful (Charter, Autozone, NVR) but you’re exposing yourself more to general market factors. A buyback model can create enormous wealth over time if the company continuously trades at only a modest multiple to FCF. It works less well going forward when the stock rockets upwards (like Apple tripling in the last 2 years - who’s complaining about that though...). Good serial acquirers with strong moats in their capital allocation processes can generally keep chugging along regardless of broader market factors. Which again helps to keep the compounding going tax efficiently for a long time.

An example of a perennial serial acquirer we really like is the Bergman & Beving group (B&B) in the Nordics. It has, over the decades, spawned an ecosystem of fantastic serial acquirers in Sweden and has, via the power of local knowledge spillovers1, single-handedly elevated the capital allocation standards in Sweden (there are lots of good serial acquirers in that country! - more to come on this soon...).

Here are the facts: B&B is a trading company for technical products in the industrial space in Sweden that was founded in 1906 and listed in 1976. It began rolling up businesses in the 1970s and in 2001 split itself into 3 independent, listed entities: AddTech, Lagercrantz, and the Bergman & Beving remain-co. AddTech itself spun off AddLife in 2016 and the Bergman & Beving remain-co has since then split itself into Bergman & Beving and Momentum Group. Malone and Diller would be proud of all that action...

B&B compounded at ~13% from 1989 (earliest data we have) to 2001 at which point the split occurred. From 2001 to early 2021 it compounded at ~10% per year. Momentum Group, which B&B spun out in 2017, has CAGR’d at ~22% since then. AddTech itself CAGR’d at 21.5% from 2001 to Oct. 2016 when the AddLife spin occurred, and continued to CAGR at 34% from that day until today. AddLife has CAGR’d at 50% since its spin in Oct. 2016 to today. Lagercrantz has CAGR’d at a cool ~21% since its spin in 2001 to today. If you invested in B&B on Dec. 30, 1999 and held all of the spin-shares, you’d be up ~38x. A 20% CAGR for 20 years. This group has compounded capital for decades with no end in sight! Not shabby for a constellation 😉 of very diverse, niche businesses. So, the allure is obvious.

Diminishing Returns to M&A

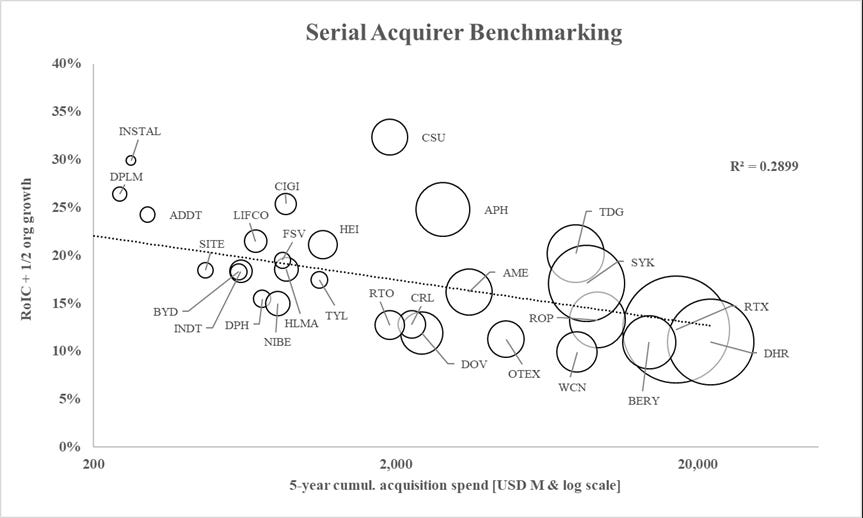

bubble size = amount of EBITDA, USD

X axis = log scale of cumulative M&A spend over the past 5 years

Y axis = ROIC + 50% of organic revenue growth

You don’t need the help of the line of best fit in the chart to be able to tell that things go downhill as serial acquirers age and the amount of cash flow available for reinvestment gets larger.

The issues at hand are that

(1) it’s simply very difficult to scale M&A if you go after a broad TAM (platforms, accumulators), and,

(2) narrower TAMs can get very competitive and excess returns can get competed away (roll-ups, portfolios).

At Danaher or Roper’s scale, it’s quite hard to bust out a double digit long-term RoIC when your average deal size is 500M to a billion dollars with average EV/ EBITAs closing in on 20x.

That leads to the basic, but powerful, law of diminishing returns to M&A:

As a) average deal sizes grow and b) the amount of annual cash flow that must be reinvested grows, incremental returns on capital decline.

-----

Oversimplification can be dangerous and reducing any group of companies, especially across industries, to a few metrics is usually not very helpful. However, there are two powerful metrics that, taken together, can tell us a lot about most serial acquirers. Those metrics are (1) cumulative spend on M&A over a multi-year period, and (2) RoIC + ½ organic revenue growth. That’s what’s plotted in the chart above, for a number of high-quality serial acquirers.

Note: We’ll save you the behind-the-scenes modelling. The reason we use ½ organic growth is that we’re trying to approximate deal level IRRs: i.e. day 1 FCF yield + growth post acquisition. ROIC is slightly upwards biased - historical book value reflects acquisitions made years ago, and as long as subsidiaries have decent organic growth at healthy ROTIC, this will lead to a natural increase in a company’s ROIC over time. Thus, we make an arbitrary downward adjustment in org growth to compensate. It’s not meant to be scientifically precise, just a rough proxy. (But one of us, being slightly more puritan than the other, feels better using this than simply using the Mark Leonard yardstick of ROIC + OrgGr)

‘RoIC + organic revenue growth’ is, of course, the metric that Mark Leonard at Constellation Software chose for incentive compensation.2 And his Keep Your Capital (KYC) initiative, which forces operating groups to retain a portion of their cash flow, was a way to turn up the pressure on his lieutenants to work harder to figure out a way to defy the law of diminishing return to M&A. (Instead of just sending the cash back to HQ ).

The biggest roadblock to defying the law of diminishing returns to M&A is that most serial acquirers, particularly platforms and accumulators, do not sufficiently scale the human capital involved in M&A and the structures and processes guiding them – as they get larger.

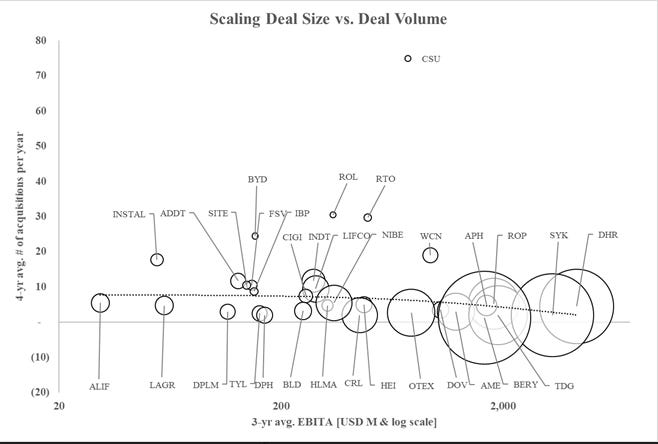

Inevitably, this lack of investment in human capital creates a bottleneck, leading them to scale by doing larger deals to move the needle rather than doing more deals. Very few serial acquirers end up scaling to more than 10 deals a year as they grow in size. The chart below shows the same serial acquirers by how many deals they do in a year (y-axis), and what the average deal size has been in millions of USD (bubble size).

This chart, together with the previous chart, encapsulates why Mark Leonard (CSU) is the GOAT.

If we look at all these companies over time, you can see that most of the lines just stay flat. There seem to be organizational bottlenecks to crossing the 10 deals per year threshold.

More (good) deals? Very hard to do. It requires a learning organization where capital allocation is a decentralized responsibility. Capital allocation being the job of only the top 1 or 2 managers in the company eventually creates bottlenecks. Larger deals? That becomes the easiest path for the vast majority of companies.

It’s worthwhile disaggregating this by serial acquirer type. Let’s exclude CSU below because it’s an outlier that’s going to skew the numbers.

Scaling of Serial Acquirers

Roll-ups

Roll-ups play in a narrower circle of competence than platforms and accumulators. SiteOne focuses on rolling up landscaping products distributors, Waste Connections on waste management services etc. They’re in a singular, large TAM that’s likely far bigger than any one of the many individual TAMs that platforms and accumulators are after. This means they don’t have to expand their circle of competence much whereas platforms and accumulators grow up in a tougher environment, constantly having to expand their circle of competence to create a new TAM for themselves.

If you wanted to draw an analogy to investing in public equity markets, you’d say that roll-ups are the expert sector analysts of the serial acquirer world whereas accumulators and platforms are the generalist investors. Playing in a single industry and/or a single country means that the companies that roll-ups buy are quite homogeneous and very similar to their existing business. This makes it a lot easier for roll-ups to tick off the quantitative boxes by comparing the target’s financials to their own base rates and their intimate knowledge of industry KPIs. Then, confirm the qualitative factors by harnessing the on-the-ground intelligence within their organization and combining it with the industry scuttlebutt that they’re privy to. Lastly, integrate the companies relatively quickly by absorption into existing oversight structures.

One of SiteOne’s 50+ acquired subsidiaries usually has intel on the next acquisition target, and quite likely recommended the acquisition target in the first place.

This is vastly different to Lifco, AddTech or Halma which are hunting for niche businesses where the details are frequently totally different from those of any existing portfolio company. Platforms and accumulators are the fundamental, bottom-up investors, having to go up the learning curve and inch outward their circle of competence for many new acquisitions. It’s no surprise then that there are a fair number of roll-ups that manage to crack closing 20+ deals a year – pest control, waste management, and collision repair shops are a few that come to mind – whereas the best platforms and accumulators rarely stay materially above 10-12 deals a year over a multi-year period.

So, roll-ups have an easier time scaling up M&A, and they can scale up deal volume pretty quickly… until they run into TAM constraints, at which point mediocrity will set in. This is a classic trap for investors looking through the rear-view mirror. Waste management, pest control, and towers are a few industries where multiples on new deals are getting very lofty (in other words, lower returns on incremental capital).

A roll-up model at the end of its useful life creates bad incentives for mgmt. For a company used to growing a lot via M&A, it’s hard to suddenly pivot to returning capital. M&A and growth is too strong a part of the culture. The main risks now become quickly falling RoIC (Rentokil), international di-worsification (American Tower? – the jury is still out), business di-worsification (Crown Castle with small cells, Stericycle with Shred-It, DaVita’s horrendous HCP deal), or, worst of all, going down the quality spectrum to purchase empty calorie revenue (Terminix).

This is an almost inevitable outcome for roll-ups by the time they get to 20-30% market share. There are often low barriers to entry and scale for anyone with capital, meaning plenty of imitators enter the roll-up fray, so by the time the leader is at 20-30%, a large chunk of the other 70-80% is held by several other large roll-ups as well. PE players will use more leverage to juice the equity returns, pushing up EV/ EBITDA multiples even higher.

After 15-20 years of very accretive purchases of independent dialysis clinics, DaVita’s share in the US got to ~35% (with Fresenius having another 35%-40%). Shareholders at DaVita would’ve been much better off if DVA had then transitioned into being a constant, aggressive repurchaser of shares like Autozone. Instead, the company destroyed tremendous value and the trust its mgmt had built up with investors over 15+ years on a very large “transformational” acquisition unrelated to dialysis.

Once the market share of the top 1-5 consolidators gets high in their lucrative home market – and we’re talking about market share relative to companies you *want* to acquire, not the kind of low quality firms Terminix is buying – it’s probably time to move on unless you’re very sure that the new market is really, really good. And often you won’t find out conclusively for quite a while whether it’s really as good as management claims it to be.

Platforms

Platforms are a decent compromise. It’s kind of like TAM expansion at a reasonable price, or TEARP (that really doesn’t roll off the tongue…). You make a larger platform acquisition, allowing you to deploy a lot of capital in one shot, then tack on a bunch of bolt-ons subsequently to drive the average RoIC back up. If you’re opportunistic with the platform acquisitions and don’t pay an arm and a leg to get into new TAMs, it can truly be the best of both worlds.

FirstService has been a great executor of this approach, having put together 5 separate platforms of material size. They got into fire safety at a great price back in 2016 with Century Fire. Most recently, in 2019, FSV did an opportunistic purchase of Global Restoration, which has the potential to pair really well with their Paul Davis business. The other platforms include residential property management, property services franchises (painting, home inspection) and design (California Closets, Flooring Coverings Intl). The different platforms, each in pretty fragmented industries, and with focused and independent management teams, should provide opportunities for high ROIC tuck-ins for the next decade.

If you find a Platform serial acquirer that’s not only good at adding new platforms but also pushes bolt-on capital allocation down to the platform level, it’s likely a really special company (FSV!).

Diploma used to fall into this category…‘used to’ because the CEO and CFO, who did the platform deals, retired over the last several years, so we are going to have to wait a bit more to find out how good Johnny Thomson turns out to be. Halma on the other hand feels a bit like it’s snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. It has the M&A teams staffed up at the sector levels with deal flow coming up from the operating companies, but, by various accounts, top management’s quality standards are so steep and their desire for control so high such that lots of promising deals get killed off. Unless something changes there, we doubt they’re ever going to scale M&A at attractive prices.

The thing to look out for with platform serial acquirers then is (a) the extent to which they have proven themselves to be opportunistic in the purchase of additional platforms in the past, and (b) their flexibility as well as embedded organizational trust in delegating the bolt-on M&A further down the organization without the head honcho insisting on being a major bottleneck.

Accumulators

Accumulators have a very low TAM constraint as they go after niche markets in a broad set of industries. Obviously if your criterion is high quality niche business and you’re not after integration or synergies, the world’s your oyster.

But accumulators play a tough game. The more heterogeneous their acquisition targets, the harder they have to work and the more paranoid they have to be to ensure that they understand all the nuances of the industry and that there are no hidden issues beneath the surface. Accumulators also usually can’t draw on intelligence within the company to evaluate the target, like a roll-up and platform can. Accumulators initially start out with a talented capital allocator at the helm who eventually becomes a bottleneck to further scaling deal volume and has to train other capital allocators within the company to do deals. (if the goal is to avoid switching to scaling via larger deals). 5 deals a year is not that big of a challenge, 10 deals a year isn’t easy but still doable, 15 deals a year or more requires a lot more than a one-man show. As covered thoroughly at this point, large deals, especially for an accumulator with little in the way of synergies, are the fastest path to mediocre returns on incremental capital, which is definitely not what we’re after.

As any investor knows, capital allocation based on a lot of qualitative analysis is something that’s very hard to teach. It requires experience (putting in the reps), humility, an ongoing desire to learn from mistakes (both yours and others), and a healthy dose of good judgement. Within the context of a team, it requires a lot of trust. The Halma example shows that this can’t be taken for granted.

While buying small private companies is one of the few places globally where “cheap multiple” value-investing is still working these days, things have definitely gotten tougher. As per one accumulator CEO we spoke to recently, whereas 7-10 years ago you could just show up to an auction and buy decent companies at good prices, now you have to massively expand your funnel and work three times as hard to get that same deal volume done.

We see it personally. If you talk to business brokers or reach out directly to some small businesses – you’re probably the 10th guy calling them in the last year alone, especially in major cities. Thanks to public successes like CSU and Brent Beshore, every third business school grad with access to a tiny amount of capital wants to buy a VMS or a local services company. (Us included!)

The competitive pressure for an accumulator to build up the M&A team, put processes in place, and develop best practices around target discovery, relationship management, due diligence, valuation, integration, and ongoing monitoring, has gone way up. Being excellent at all of the above is a hard, slow and deliberate process – it takes many years to reap the seeds you sow.

Evaluating and monitoring accumulators’ progress in positioning themselves for long-term scalability of capital allocation is an important task. Especially for accumulators that have crossed the size threshold at which 10 deals a year or more are required to move the needle.

Constellation Software

Constellation Software is the Michael Jordan of serial acquirers. (In this case, Thomson Newspapers was likely the Wilt Chamberlain - we may eventually write up a study of Thomson)

CSU has a lot of the characteristics of an accumulator but completely defies accumulator base rates. It’s a combination of best execution meeting an ideal industry (VMS) to roll up.

Here’s what makes VMS unique:

There are tens of thousands of VMS businesses around the world, meaning a huge number of niche TAMs to go after (tons of submarkets within industries such as transportation, healthcare, payments, education etc. etc.). While there are key differences based on end-market, customer type etc., those different VMS TAMs are still a lot more homogeneous than the TAMs that most accumulators and platforms target. Homogeneity in turn is key to develop some standardization and best practises in the M&A process, which you need in order to push M&A down the organization and scale deal volume.

The average VMS business is a very good business. VMS has solid unit economics (requiring negative tangible capital when done right) as well as pricing power (lots of mission critical software out there), and the business resilience remains very strong even as you go downmarket into small enterprises given the inherent switching costs and recurring revenues. That last part is very important – small businesses sell at lower multiples for a reason… in most industries, size provides vastly more resilience via all sorts of diversification (internal talent, customer, product, end-market, etc.). Most small enterprises are just owners with jobs in corporate ownership form. (read Brent Beshore’s blog). In VMS, you can acquire small businesses at attractive multiples and still get decent business resilience with high retention rates and cash that comes in no matter what’s happening in the world. Fishing in a pond with lots of fat healthy fish vastly reduces the odds that you’re accidentally buying a turnaround project, and small deal sizes (each transaction is immaterial individually) mean you just have to be right on average, both of which make it easier to push M&A down the organization.

Constellation has seized a vast number of VMS TAMs globally. How Constellation catalogues VMS businesses, nurtures relationships with owners, applies its treasure trove of base-rate data to value them, integrates them (very lightly - letting basic behavioural finance principles do most of the work), monitors them, and makes improvements based on its best practice playbooks (especially around pricing) is the same no matter what country or industry. Closing 100 deals a year may sound like a lot (and it is a huge accomplishment), but if you put it relative to the tens of thousands of companies in its proprietary database that it draws these acquisitions from, and likely many dozens of M&A people working on these deals, sustainability and continued scalability is a lot more achievable than your instinct may tell you at first.

Constellation still has to train its internal capital allocators. There’s no way around that. Pushing capital allocation further down the organization is not without risk, but it’s a vastly lower risk game if you are a capital allocator at Constellation. You’re buying fairly robust businesses within a category (software) you understand, guided by the base rates of hundreds of past acquisitions and a treasure trove of due diligence and deal structure best practices. It’s got some shades of a roll-up.

Other serial acquirers, like Halma, have to learn about the intricacies of crawler cameras deployed in inspection of UK water companies’ pipes one month, followed by precision radiometric and photometric systems for light testing, calibration and measurement the next. They face difficult hurdles in scaling up.

If, like CSU, a firm closes 100 deals a year rather than 5 (especially if the 100 are mostly all individually pretty small), the law of large numbers also smooths out a lot of dispersion of outcomes among the individual transactions. Individual outcomes will vary widely from the base rates, but all transactions are individually immaterial and in aggregate will get very close to the base rates.

What to look for

Roll-ups

It’s key to have a good sense what the actual roll-up TAM is. If management teams tell you how many companies are in their industry, and thus purported acquisition targets, you need to figure out what percentage of them are realistic acquisition targets, so excluding the crappy ones, tiny ones etc.

Then you need to have a sense of what share the roll-up, as well as the other roll-ups, both public and private, have within this realistic TAM. If this concentration starts getting high by your estimation and annual EV/ EBITA multiples paid by the roll-up are steadily going up, it may be time to move on, especially if you have even the slightest concerns around management’s TAM expansion approach. None of this is rocket science, but we tend to get lazy and just go with management’s numbers, justifications, and stories (especially if the stock price continues to go up), instead of thinking for ourselves.

Platforms & Accumulators

Smaller is better. A small accumulator or platform just needs to have the basics right – a focus on asset-light businesses with recurring revenue in a GDP+ growth industry, a smart, hard-working management team with a disciplined valuation approach, a good incentive structure, a decentralized organizational model, and good oversight over the acquired businesses. If they meet these criteria and they’re small enough such that 5 deals a year add material growth, they can grow into their multiples even if they never scale above 10 deals a year.

For medium-sized platforms or accumulators, like a First Service, Halma or Lifco, you want to make sure they are seriously thinking about scaling deal volume (or intelligently adding new platforms). They need to be working on this. If that’s the case, you can still pay a full multiple and do well over the long term.

For large platforms or accumulators, like a Roper or Danaher, it’s probably more a question of entry multiples. If you want to compound at 12%-15%, you have to keep in mind that at that size, mgmt probably can’t reinvest at un-levered returns much higher than 10%. So far, the equity returns have continued to be okay because the cost of debt is so low, but ROICs are no longer exceptional.

Summary

High quality serial acquirers make for fantastic investments as they can redeploy capital on your behalf for many, many years while simultaneously becoming more diversified/less risky.

Scalability is a key criterion you need to evaluate when looking at a serial acquirer. The diminishing returns to M&A can only be delayed, not escaped, and scaling is a slow, deliberate process.

Roll-ups, platforms and accumulators all have their own opportunities and risks to look out for as it pertains to scaling.

Investing in larger serial acquirers with a track record may provide a false sense of security. A rear-view mirror approach is often inappropriate because dis-economies of scale are real and what’s required to scale over the next 10 years probably isn’t like what was required to scale over the last 10 years. Simply put, smaller and more fragmented is generally better for all three: roll-ups, platforms and accumulators.

An accumulator that is thoughtfully scaling their M&A infrastructure and processes is extremely valuable.

CSU is the GOAT !

Book recommendation: The New Geography of Jobs

See Constellation Software president letters for more info on the topic. What we refer to as “RoIC”, Mark Leonard calls “EBITA Returns”. Mark’s definition of “RoIC” in his 2015 letter is a levered measure, i.e. return on equity. https://www.csisoftware.com/docs/default-source/investor-relations/presidents-letter/pl_2015.pdf

Superb read. What matters is RoIIC and Reinvestmate Rate. Growth is a product of these two. Thanks so much Canuck.

By far the best write up I have read on Serial Acquirers..Thank you for sharing!